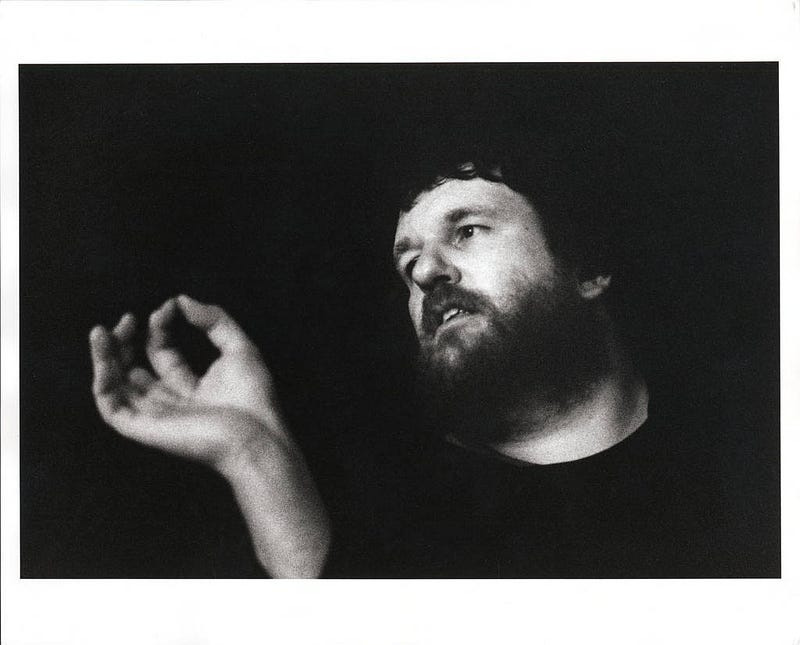

WHEN AN ARTIST DIES, IN AN INSTANT, their oeuvre suddenly becomes complete and is forever frozen in amber. Their life and work is now seen from above as a long timeline, with recent works now deemed to be part of a newly created “late period.” Death casts a shadow over these last few works in retrospect. Micro eras and styles will then be categorized to form a cohesive creative narrative. Suddenly, pieces which were once seen as disparate works are now part of a “middle period.” When the British composer and conductor Oliver Knussen died in the summer of 2018, his passing felt more like a cliffhanger rather than a clear finale. One reason was that he died relatively young, only 66 years old, though he did struggle for years with a series of health issues. Another was that so many of his pieces were left incomplete. One of Knussen’s compositional hallmarks was his ability to create intricate and richly detailed scores, mostly for large ensembles and orchestras. The flip side of being a detail obsessed artist is that the creation of a single work progresses slowly and methodically.

Major orchestras and solo artists knew that when you commissioned a work from Knussen, there was a good chance that the work would come in drips and drabs, in most cases over the course of years if not decades past the original due date. When he died, he left behind, in various stages of development, a piano concerto for Peter Serkin and the London Sinfonetta (slated for a premiere in 2001), a fourth symphony for the New York Philharmonic and conductor Lorin Maazel (2004), a cello concerto for Anssi Karttunen and the Los Angeles Philharmonic (2013), as well as other commissions from the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Ojai Festival.

Yet another work left on the drawing board was a nearly complete orchestral work commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra, an organization Knussen worked with extensively as a conductor for decades. The seven movement piece, Cleveland Pictures, was scheduled to be premiered by the orchestra and their music director Franz Welser-Most over a decade ago in March of 2009. Indeed, even that March 12, 2009 concert date was the third time the world premiere had been shifted around since the piece had been commissioned back in 1999. But now, at long last, Cleveland Pictures will receive its world premiere on June 24, 2022 at the Aldeburgh Festival with Ryan Wigglesworth leading the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Coming in at roughly 16 minutes, Cleveland Pictures will be one of Knussen’s most substantial pieces for orchestra. This is, after all, from a composer whose three symphonies average around 15 minutes in length. This will also be his first large scale, stand alone orchestra piece since his 1979 Symphony №3. Cleveland Pictures is a sort of modern day riff on Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, with Knussen musically responding to seven works of art from the Cleveland Museum of Art. Knussen’s inspiration’s for the piece range from a sculpture by Rodin, paintings by Turner and Goya, and two small Tiffany and Fabergé clocks. Of the seven planned movements, four are complete, two are in the form of fully-orchestrated fragments, and one, a response to Masson’s Don Quixote and the Chariot of Death, exists as a 10-bar sketch.

Unlike other composers whose works were premiered posthumously, Knussen was able to both hear large portions of Cleveland Pictures performed and tweak some of the movements over the years. He conducted a reading of the piece in January of 2008 with the New World Symphony and Cleveland Orchestra in Miami, a year prior to the scheduled world premeire in Cleveland. They played through four or five movements, each lasting roughly two to three minutes. Cleveland’s principal flutist Joshua Smith, who played through the excerpts, said at the time that it “was my feeling that we played was complete. But he [Knussen] told us he wasn’t sure about what direction he was going to take from there. It’s hard to get a read from him on how he’s feeling. He’s constantly self-deprecating.” Those at the workshop recall Knussen’s musical take on Turner’s The Burning of the House of Lords and Commons as “lush and dramatic,” and the “irregular twittering” of Faberg’s Kremlin Tower Clock.

The premiere performance of Cleveland Pictures will be broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 alongside Knussen’s Horn Concerto, a homage to Mahlerian night music, as well as Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Cleveland Pictures older sibling.

The press release announcing this summer’s premiere of Cleveland Pictures stressed the point that the work will remain unfinished and be performed as is. Sam Wigglesworth, the Director of Performance Music at Faber Music, Knussen’s publisher, wrote “throughout the many painstaking discussions that have led to this point, Sonya Knussen and I have always been united in our belief that every note of these extraordinarily vivid orchestral pieces must be presented exactly as Knussen left them — with no interventions or attempts at completion. Knussen’s music, in all its meticulous artistry and dazzling invention, speaks for itself.”

The question of what to do with unfinished pieces has been a point of debate with musicologists, performers, and music lovers for as long as there has been unfinished pieces. There is a fascination with the idea of what might have been? When listening to Deryck Cooke’s 1964 configuration of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, one can hear early traces of the Second Viennese School, specifically his friend Alban Berg. What direction would Mahler’s music take if he lived to compose a fourteenth symphony? With his high profile stints as music director of major opera houses, what would a Mahler opera sound like?

These are engaging intellectual exercises, but ultimately, they are dead ends.

There are essentially two broad choices of what to do with unfinished work: leave it as is or attempt to complete it. Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus is centered around an incomplete work, Mozart’s Requiem, which was later completed by various composers in numerous editions. Puccini’s last opera Turandot was left unfinished, with radical choose-your-own-adventure completions, first, by the Italian composer Franco Alfano and later by, of all people, the modern and experimental composer Luciano Berio. In the “leave it as is” camp, Alban Berg’s widow lived out the remaining forty-one years of her life ensuring that no one complete her husband’s unfinished opera Lulu. Jacob Druckman worked for over a decade — I would argue as far back as the late 1970s — on his opera Medea which was left unfinished when he died in 1996, receiving only a one-act read through with a rehearsal pianist at Julliard. The piece exists only in the form of an unorchestrated first act and sketches of a second in his archive at the New York Public Library.

The choice to complete an unfinished work, needless to say, opens up some problems. To continue down the Mahler Tenth Symphony road, what Deryck Cooke did was assemble drafts and sketches into a cohesive symphonic form, relying heavily on Mahler’s past work to inform the creation of a new one. In many ways, what Cooke did was a highly informed guessing game, and a very conservative one at that. In relying too much on one composer’s past work, the assembling of a new work can fall into a paint by numbers approach, creating a piece which neatly emerges from the previous one. Mahler’s Tenth, as the sketches suggest, represent what would have been a new chapter, especially in terms of Mahler’s approach to harmony. Mahler saw his Ninth Symphony as the end of a symphonic cycle — and to that point, the end of his life, full stop — so it would make logical sense that the Tenth would almost be a rebirth. Leaving the task of completing a work like Mahler’s Tenth, one that would have radically broke with the past (or would it?) to anyone other than the composer himself, is a lost cause. It is one thing to present fragments of unfinished work, some of which has been assembled and completed by an expert or former student. But, in my opinion, it is quite another to “finish” a piece.

A FASCINATING CASE STUDY IN WHAT TO DO with posthumous work, as well as work that was completed and still tampered with, would be the other composer sharing the bill on the Cleveland Pictures program this week, Mussorgsky. His progressive, innovative harmonies and approach to orchestration were seen by many, including his own colleagues and teachers, as faulty, amateurish, and in desperate need of tidying up. His teacher Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that his music contained “absurd, disconnected harmony, ugly part-writing, sometimes strikingly illogical modulation, sometimes a depressing lack of it, and an unsuccessful scoring of orchestral things.” These same qualities which frustrated his contemporaries made him a favorite of composers a generation or two ahead of him: Ravel, Debussy, and Stravinsky. The orchestration in his opera Boris Godunov, for instance, is still seen by some to be too thin and too nasally at times. It lacks the grand and robust scoring an epic Russian opera deserves. Thus, many of Mussorgsky’s pieces, both complete and incomplete, have been subjected to dramatic and substantial edits, re-orchestrations, and in the case of his operas, additions and substitutions of scenes and full acts.

There are few works by Mussorgsky that haven't been changed either during his lifetime or after. Just to take his most famous works: Pictures at an Exhibition, originally a suite of pieces for solo piano, lives its life out now primarily as an orchestral work orchestrated by Maurice Ravel (with nearly twenty other versions by Leopold Stokowski, Henry Wood, and others).

Night on Bald Mountain, made famous in popular culture by Disney’s Fantasia which gave all children nightmares for decades, is primarily known as an orchestral piece severely edited by Rimsky-Korsakov as well as another version by Stokowski (not to mention the true masterwork, Night on Disco Mountain, David Shire’s take on Mussorgsky from Saturday Night Fever).

And his masterpiece, Boris Godunov, lives on in three versions, with different scenes and orchestrations. The one edition of the three which is most rarely performed is the one exclusively by Mussorgsky. This is not to mention the works that were left truly unfinished like his opera Khovanshcina, which has several completed versions; first by Rimsky-Korsakov, then by Maurice Ravel and Igor Stravinsky in 1913, and later by Dmitri Shostakovich in the late 1950s. Mussorgsky’s earlier unfinished opera, Marriage, was completed in a version by, of all people, Oliver Knussen.

This is all to say that in the last few decades, there has been a sort of Mussorgsky originalist movement. The argument is that in “correcting” all of these pieces, one is left with a Mussorgsky without the nuanced quirks. After all, these harmonic and orchestrational choices seen as wrong at the time directly influenced some of the most important composers of the 20th century. There are so many countless edits and revisions by composers not named Modest Mussorgsky, that it takes a fair amount of archeological digging to get to what is truly Mussorgsky’s own music. It is a strong argument to keep music as is; to keep weird music weird.

Though I would love, to the point of nearly seething, to hear a complete performance of Oliver Knussen’s piano concerto or his Fourth Symphony. But, even if that were to happen, I would not be hearing Knussen’s piano concerto or Fourth Symphony. I would be hearing a patchwork of sketches in an order unfamiliar to the composer, and likely, with orchestration alien to Knussen. To the contrary, when I hear his Cleveland Pictures, I will be hearing Knussen; his choices, his edits, his fragments which he never got around to orchestrating. I’ll know that this 10-bar Don Quixote sketch was a musical problem for him, something he either never got around to fleshing out or didn’t know what to do with it.

When we all have access to nearly every piece ever composed at the click of a button, death reminds us, that there are still some things that we will never be able to access. Hard as we try, we won’t know what Mahler would have done with his Tenth Symphony or what Mussorgsky would have done with Khovanshcina. The finality of these things is a kind of beauty in and of itself.