REMINISCING WITH BERNSTEIN

Listening Back To A Childhood Idol

IN THE SUMMER OF 2012, I ATTENDED A SUMMER MUSIC FESTIVAL in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, and for the first time found myself encountering and engaging with other musicians and composers. Of course, there were band kids and budding singer-songwriter types in my high school, but at this summer institute, you had complete musical obsessives—teenagers who would flamboyantly debate the ranking of Shostakovich symphonies and Beethoven piano sonatas. I knew I had found my tribe.

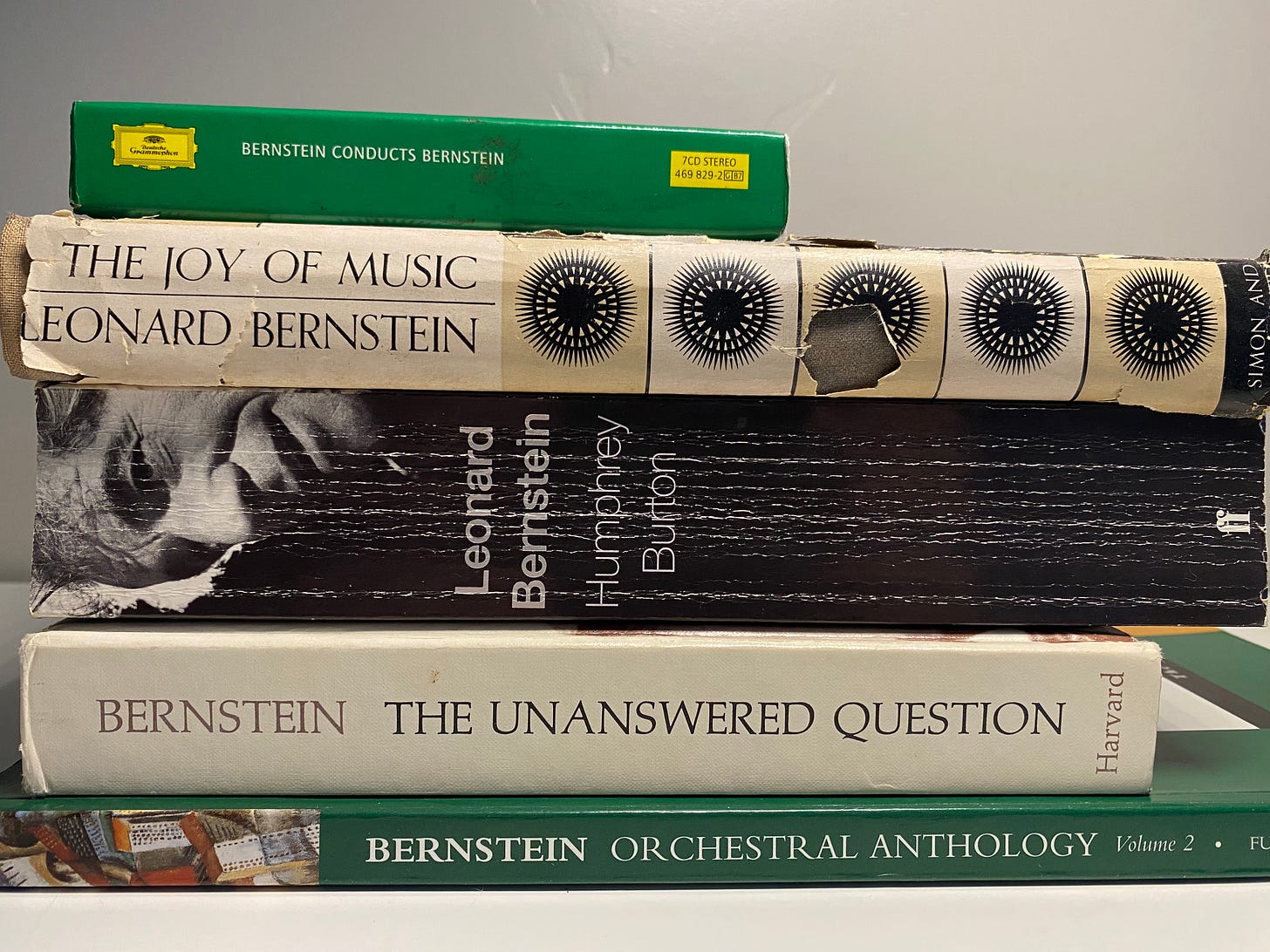

I was at the festival as a composition student, the youngest in a group of, give or take, a dozen other composers. As part of our first daily composer forum, each of us had to present two pieces of music to the assembled body: one of our own and another by a composer for whom we felt a particular fondness. Choosing the latter piece was a no brainier. All throughout my time in high school, I was obsessed with the music of Leonard Bernstein. For a recent birthday, I had received a DVD of Bernstein’s television lectures for the CBS series Omnibus, a Deutsche Grammophon box set of his orchestral music, and a score of his Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront. Whatever Beyoncé or Taylor Swift was to others in my peer group back at school (this is embarrassing, I cannot think of a contemporary teen idol of my own generation), Leonard Bernstein was to me.

The obsession felt like something that was uniquely mine, like most high school obsessions are. A teenager who sleeps every night in a bedroom plastered with posters of musicians or athletes believes they have the true key to understanding their idols and heroes. My horse-blinder vision led me to believe that there wasn’t another human alive who understood Leonard Bernstein like I did, though this man had died four years before I was even born. In him, I sensed a kindred spirit. Here was a man passionate about music and teaching in equal measure, a type of hybrid life I wanted to pursue. I loved the unabashed enthusiasm that seemed to run through his entire body when talking to an audience about Beethoven’s Third Symphony or Berlioz’s Symphonie-Fanastique. The passion was infectious. It also didn’t hurt that unlike other possible role models, this one had movie star good looks and charisma.

In his music, I loved the sharp bite of his harmonic arsenal, mostly made up of half-steps and tri-tones. I grooved, sometimes literally conducting the music in my bedroom, to his jagged, uneven Stravinskian meters which seemed to shift with every bar. That is not to say that his music did not also contain moments of sublime lyricism. And as a classical music convert who came to the form by way of musical theatre, I loved the music’s intrinsic theatricality. The gestures, of both the music and the man, were often huge and brash. They were all one thing or all another. His music and his life lived at the extremes.

There is not a single doubt in my mind that the singular figure that led me towards this endless deep dive into the world of music was Leonard Bernstein.

So I proudly shared my favorite piece to the group of composers, Bernstein’s 1971 “theatre piece for singers, players, and dancers,” Mass. I admittedly had no idea how unanimously loathed this piece was. Loathed might be a strong word. Let’s say eyeroll-inducing. The piece is a massive, perhaps overstuffed, cross-genre evening-length work for choir and orchestra… and rock band and musical theatre singers and dancers and marching band and more that probably escapes my mind. Like Stephen Schwartz—who came in late to the project to contribute some additional lyrics—and his musical of the same year Godspell, Mass deconstructs and thumbs its nose at the traditional Catholic rites with more than enough post–Summer of Love sentiment. Throughout the work, there are some moments of heartfelt tenderness, the concluding Communion canon that gloriously spreads through the singers and orchestra, and some moments of bar stool religious philosophy (“I believe in God, but does God believe in me?”).

The composers in the group first slowly, then all at once, began the piling on. One, a doctoral student, piped up. “I… admittedly hate this piece.” That seemed to open the door. The director of the program began a good faith crusade to convince the group that there were some redeeming factors in the piece, to not much success. It was my first experience of seeing how my cloistered musical opinions fit with others. My heart wasn’t smashed and I didn’t rip down those mental posters. I still felt secure and confident in my musical tastes. But like all of us with our first passions, I had seen Bernstein outside of myself for the first time and in the light of the larger musical world.

So now twelve years later and in light of Bradley Cooper’s new film about Bernstein, Maestro, I decided to dust off (almost literally) my Bernstein discs and books and go back to a childhood hero with fresh if not somewhat new ears.

AS A MUSICAL THEATRE CHILD WHO CAME TO CLASSICAL MUSIC IN my teens, it was oddly not Bernstein’s musicals that drew me into his symphonies and orchestral works. I of course knew West Side Story, perhaps one of a handful of near-perfect Broadway scores, and have found a deep fondness in recent years for the quasi-conversational nature of songs like “A Little Bit in Love” or “Some Other Time” with their wonderful musicalized sighs and moans. But for me it was his Second Symphony “The Age of Anxiety,” which just happened to share space on a disc with the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, that brought me into the Bernstein orchestral oeuvre. The latter work functioned as a musical gateway drug; the twenty or so minutes of wordless, though richly lyrical, orchestral music groomed me for the longer, perhaps more sophisticated, mid-century symphony. The Age of Anxiety is really a symphony in name only. An audience member who arrives late to a performance would be forgiven for assuming that the piano in front of the orchestra, as well as the lengthy solo passages, were part of some kind of piano concerto. Bernstein’s Second Symphony is much like Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony, a large “symphony” but with robust solos for piano. (Bernstein conducted the world premiere of the Turangalila Symphony in Boston, later snidely calling it “coffee table music.”)

Written in 1949 when Bernstein was around thirty, The Age of Anxiety musically shadows W.H. Auden’s 1948 poem of the same name. The structure of the symphony and the relationship between instruments mirror the four central characters of Auden’s poem who sit together in a wartime New York bar pondering the apocalyptic future. The musical link between Bernstein’s Second Symphony and West Side Story is the attempt to fuse what Bernstein seemed to believe were two genres that culturally existed at polar opposites: classical music and jazz. High art and low art. In the long struggle to find a quintessential American Symphonic Sound™, American composers musically tried nearly everything on for size, but all roads seemed to lead, as most nationalistic styles do, back to the country’s folk music. This was Dvorak’s solution in his “New World” Symphony as well as Charles Ives’s in nearly his entire output. And the idea of jazz and blues as being a kind of American folk music itself began to crop up in the work of George Gershwin and in the early music of Bernstein’s friend and compositional mentor, Aaron Copland.

Musically, Bernstein was cut out of Copland’s cloth. Listening to Copland’s music, it’s hard not to hear, retrospectively of course, fragments of Leonard Bernstein. Shockingly similar fragments! About a minute into the second movement of Copland’s Piano Concerto from 1927, the piano introduces a theme, an oscillating group of four beats and three beats, which will eventually become the tail end of the Presto barbaro from Bernstein’s score to the film On the Waterfront. About thirty seconds later into the Copland, and the music morphs into the opening of “New York, New York” from On The Town, in the same key. In Copland’s early music, he had found a unique hybrid musical language between elements of the modernist wave coming from Paris and the folk music of his country, namely jazz. Bernstein would in a sense attempt to rediscover a musical solution already established quite successfully by Copland and Gershwin among others. What Bernstein would eventually add to this language was a brashness, a kind of brute violence to the rhythmic and harmonic profile curated by the generation before him.

I had listened to this Second Symphony and Symphonic Dances from West Side Story disc routinely before reaching the point when I had to find a local music library and see the music itself. I was in high school, just on the cusp of the “everything is online” generation. It is now shockingly easy to find a full orchestral score to almost any work that is not yet in the public domain, either by way of a perusal score on the publisher’s website or by illegal PDF scans on the web, of which I of course have no firsthand knowledge. Over the course of years, I amassed scores by having my parents drive me, and later driving myself, the 40 minutes to the campus of UNC Chapel Hill once a month to check out four or five scores at a time from the dimly lit, musty basement music library. With the ease of a library card, I finally had access to Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms; Serenade; Divertimento for Orchestra; Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs; and the Second Symphony which had seemingly started it all. It was thrilling to traverse the alleys of the library, happen upon a lesser work of Bernstein’s, and finally see the hieroglyphics, the engine underneath the hood, of this music that had such a profound effect on me. I would usually tear through the score trying to find that one section, the one that enthralled or confused me, oftentimes both. How is that chord orchestrated and voiced? What meter is that section in? Is that harmony I crudely sketched out when listening the correct one in the score? But at that time, the library did not have the two works which were my complete, unabashed obsessions: Mass and the Third Symphony.

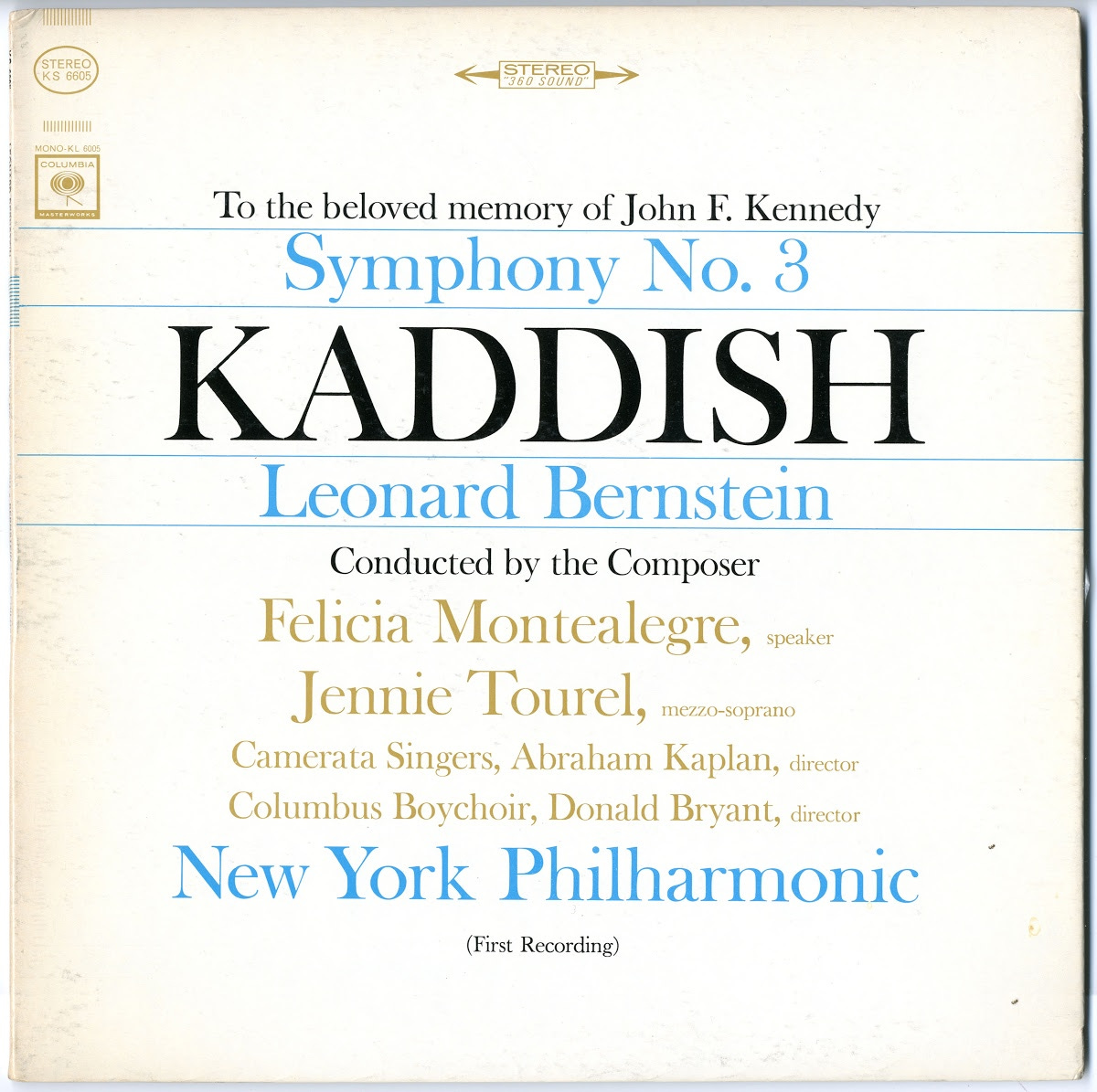

Lenny’s musical bravado and brashness come to the fore in both of these works. In the sense that Mass is a thumbing of the nose at organized religion, the Third Symphony Kaddish is a screaming match with the creator. Written “to the beloved memory of John F. Kennedy,” Kaddish is a large symphony for chorus and orchestra, as well as a narrator, who contorts through all of the stages of grief with God. There is anger (“Your covenant! Your bargain with Man! Tin God! Your bargain is tin! It crumples in my hand!”), depression (“The rainbow is fading. Our dream is over”) and acceptance (“Look. Do You see how simple and peaceful it all becomes, once you believe? Believe! Believe!”)

The quality I loved in this piece, then and now, is how overwhelmingly over-the-top it can be. The theme that sings out after the narrator shouts “Believe! Believe!” is as rich and lyrical as the opening choral romp is angular and jagged. That first jagged Kaddish has all the groove and violence of a rumble in West Side Story, all while containing, at its core, a strict twelve-tone motive. The series of Amens which are shouted by the chorus over a scampering string section are more akin to a screaming crowd at the Roman Colosseum than the prayerful closing of a doxology. That first movement moves at a blistering speed and a good performance that has both heft and speed, like Bernstein’s own with the Israel Philharmonic, takes a listener by the throat and does not let up for five electrifying minutes.

The answer to this First Kaddish is a hauntingly intimate Second Kaddish. The opening moments are reminiscent of the ambiguous introduction to Mahler’s Adagio from his Fifth Symphony, a steady harp accompaniment void of clear harmonic grounding. A soprano soloist emerges from this musical mist, singing in Hebrew, “He who maketh peace in His high places, may He make peace for us.” The solist’s line sublimely radiates and melds into the soprano and alto members of the choir, creating a carefully crafted echo. The extremes at which this piece lives, along with Mass and countless others, is what really drew me to Bernstein’s music. The music is often all one thing or all the other. This could be seen as lacking necessary artistic nuance, but to a teenager, who at that age is always one thing or the other, it provided musical whiplash in the best sense.

Years after first going to that dark music library in Chapel Hill to borrow the Second Symphony, UNC bought a copy of Bernstein’s Third Symphony around the time of my eigtheenth birthday. I quickly made the drive over, checked it out, devoted hours to just staring at it and, I’m sure, racked up enough late fees for the library to purchase several more copies if they wanted to.

IT IS A HISTORIC CLICHE TO MENTION THAT BERNSTEIN WAS A MAN of dualities. He often made this point himself when not so humbly comparing his life and career to that of Gustav Mahler. Like Mahler, Bernstein was a composer and a conductor, in self-described equal parts. He was a man of the American Musical Theatre and of the Concert World. He was an American and a Jew, who, against the advice of his mentor Serge Koussevitzky, kept his surname rather than adopting the more gentile-infused name of Leonard Burns. He was a serious public intellectual and a flamboyant, exuberant showman. Biographers described his bisexuality as a kind of duality, incorrectly in my view, as though bisexuals are tying themselves into knots over the two sexes and their preferences.

But the idea of the binary, of all one thing or the other, came to the fore in listening back to his music. There seems to be a constant battle and obsession in Bernstein’s music between what he believed were opposite poles: tonality versus atonality, American versus European, Jazz versus Classical, Musical Theatre versus Concert Music, the sacred versus the secular. There is on occasion a happy marriage between diametrically opposed idioms. But more often than not, the music seems too aware of its task: to stitch two genres together somewhat haphazardly.

Throughout this re-listening, I couldn’t shake the sense of Bernstein desperately wanting to be taken sincerely as a (scare quotes) “serious” composer. In many of his talks and lectures, be it the Young People’s Concerts or something on CBS’s Omnibus series or his Harvard Norton Lectures, he routinely made the argument that this popular notion of high art/low art was nonsense. The Beatles were just as musically interesting and sophisticated as a Neo-romantic ballet by Stravinsky, he would say. This leveling of the musical playing field was convincingly presented, but there still seemed to be a bug in Bernstein’s head, which came out in his music, that seemed to not believe what he himself was saying. Throughout his orchestral works, which span from the early 1940s to the late 1980s, there is a shadow cast by whatever flavor of the month contemporary music gesture reined supreme at the time. The opening movement of his late Concerto for Orchestra “Jubilee Games” presents a hefty handful of the aleatoric techniques of Wiltod Lutosławvski. The Third Symphony presents an array of percussion a la Edgar Varese or Jacob Druckman, but unlike those composers, the sound never quite melds.

Because of these dualities, I heard a kind of profound trepidation in Bernstein’s orchestral music. The pieces seem to acknowledge he lived on a divide in the world of contemporary music: the most sophisticated musical theatre composer, but the most simplistic and sentimental contemporary music composer. The reviews of his music demonstrate this. His symphonies and concertos were lambasted as being too overtly romantic, too heart on the sleeve. His musicals, famously in the case of the first reactions to West Side Story, were too angular and had no melody. (Though built on often neglected intervals in the canon of musical theatre, West Side Story has whistle-able tunes galore, espeically since Somewhere is note for note the first theme from the second movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto.)

Likely to Bernstein’s chagrin, re-listening to nearly everything, I came away believing that he is at his truest, most unconstrained in his musical theatre works. Like Mahler who at his core was a lieder composer, Bernstein was perhaps at his best as a songwriter. West Side Story and Candide, as the New Yorker’s Alex Ross wrote, “might have done more to advance the cause of American classical music than all of Bernstein’s concerts and broadcasts put together.” There are countless influences that do of course rise to the surface in his songs, but all feel integrated and organic. Musical theatre is, like Bernstein, made out of dualities and contradictions and genre bending. The Broadway musical itself is a hybrid art form, the mixing of European operetta and American Vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley and folk music. This cultural melting pot is what Bernstein attempted in his concert works, but nearly perfected in his musicals.

IN THIS LOOKING BACK AT BERNSTEIN AND HIS MUSIC, I WAS reminded all over again how deeply profound my obsession was. His music not only drew me deeper and deeper into his works, but because of his prolific output as a conductor, I smoothly migrated into works by Beethoven, Copland, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, Mozart, Mahler, Debussy, and Ravel. And that same enthusiasm I had for Bernstein the composer would travel to Bernstein the conductor.

There is no greater, and rarer, feeling in life than the knowledge that you have found a true obsession. There is a childlike, Christmas morning kind of enthusiasm which begins each day, almost magnetically pulling one towards learning or experiencing more. This could take the form of shooting endless three-pointers, in the case of my father, or whipping through books on old Hollywood and theatre, in the case of my mother. Everything, truly everything, is a discovery. When starting from zero, nothing is assumed and every new tidbit of information becomes a revelation.

And these moments of joyous curiosity and revelation begin to recede as you descend deeper and deeper into a specialized field. The magic of an interval or a harmony or a daring bit of orchestration becomes, with time and distance, contemplated and rationalized. There become fewer moments of awe when violently flipping through a score in the library. Like learning the “real work” behind a difficult card trick, the initial wonder and awe become dulled and the analysis begins.

Yet, it should be said, I hate, hate, hate the notion that a deeper understanding of any art (scare quotes again) “kills” the enjoyment of that artwork. Looking under the hood of a piece of music doesn’t “kill” the enjoyment of that music in the same way that learning how the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling was painted doesn’t throw out the entire experience of gazing skyward, mouth agape. There are new levels of discovery available when one has rationalized and analyzed a work of art, what the English art critic John Berger called “ways of seeing.” One finds new ways to experience a novel or symphony or mural after learning more about the work itself. Nonetheless, in some instances, the magical eventually becomes the ordinary.

But as always in great art, some elements simply defy close inspection. And I am happy to report that there are sublime moments in Bernstein’s concert works that remain indescribable to me. I still think that the momentum that propels the first movement of the Third Symphony is thrilling. I find the theme, emerging in its prime three quarters of the way through, deeply moving. Though not a stand-alone concert work, I find the Pas de deux from On the Town perhaps the truest thing he ever wrote.

The sheen has worn off on some of these pieces for me. But the rediscovery of these works reminded me of the sheer joy that came with reveling in these works years ago. I suppose we all wish that the most profound art inspired us to either become artists ourselves or become lovers of art. A novelist lies and says that it was James Joyce that made them a writer. A poet claims that it was Eliot’s The Wasteland which opened their eyes in middle school. Being honest, it is often not the highest forms of artistic achievement that spark that magical, unquenchable imagination when we are young. That bind, between that younger self and that influencial artist or writer or composer, can whittle away with time. But that sometimes obvious, sometimes fragile mark left behind, is always permanent. So as I sit here writing this, the Profanation from Leonard Bernstein’s First Symphony still dances on and on… and on in my head. And I’m so glad it is his music that still plays on.