HOW HISTORY IS WRITTEN

The Boston Massacre, January 6th, and Renee Good

I WOKE UP THIS MORNING with the American Revolution on my mind. The view outside my window today is blanketed with snow, both on my porch and on the mountains just beyond and it made me think, inevitably, about another morning, similarly cold and wintry, at the threshold of the Revolution.

The scene is familiar enough to have hardened into iconography. Amid rising tensions that had been simmering for months between the occupying British forces and civilians in Boston, a series of agitated protesters began throwing snowballs at the standing army. Soft snowballs turned to snowballs with rocks in them, which eventually turned to clubs. As the violence brought about by the protesters escalated, one British soldier fired their gun onto the crowd, leading the commanding officer to order the rest of the army to open fire. Three protesters were killed. Eight others were wounded, two of which died days later from their injuries.

I suspect this episode was on my mind because of yet another snowy day, this one in Minnesota, when a different uniformed force fired on a civilian protester. And I was struck by the odd dissonance: the Boston crowd of 1770 was, by any plain accounting, far more physically aggressive toward the soldiers it confronted than Renee Good’s ill-fated, icy three-point turn was toward the ICE officer who killed her. But no one, surely no one who is now blaming Ms. Good for her own murder, would even suggest that the Boston Massacre was in some sense brought about by the protesters.

History, as it is said, is written by the winners. The American Revolution is not The Great British War of 1776 because the Americans were the victors and wrote the history. Similarly, we do not call what happened on that snowy day in March of 1770 the Boston Tussle, or the Boston Escalation. We call it the Boston Massacre. The winning narrative is that the British emerge as agents of imperial brutality; the colonists as martyrs to liberty. Victory confers not just power, but narrative authority.

§

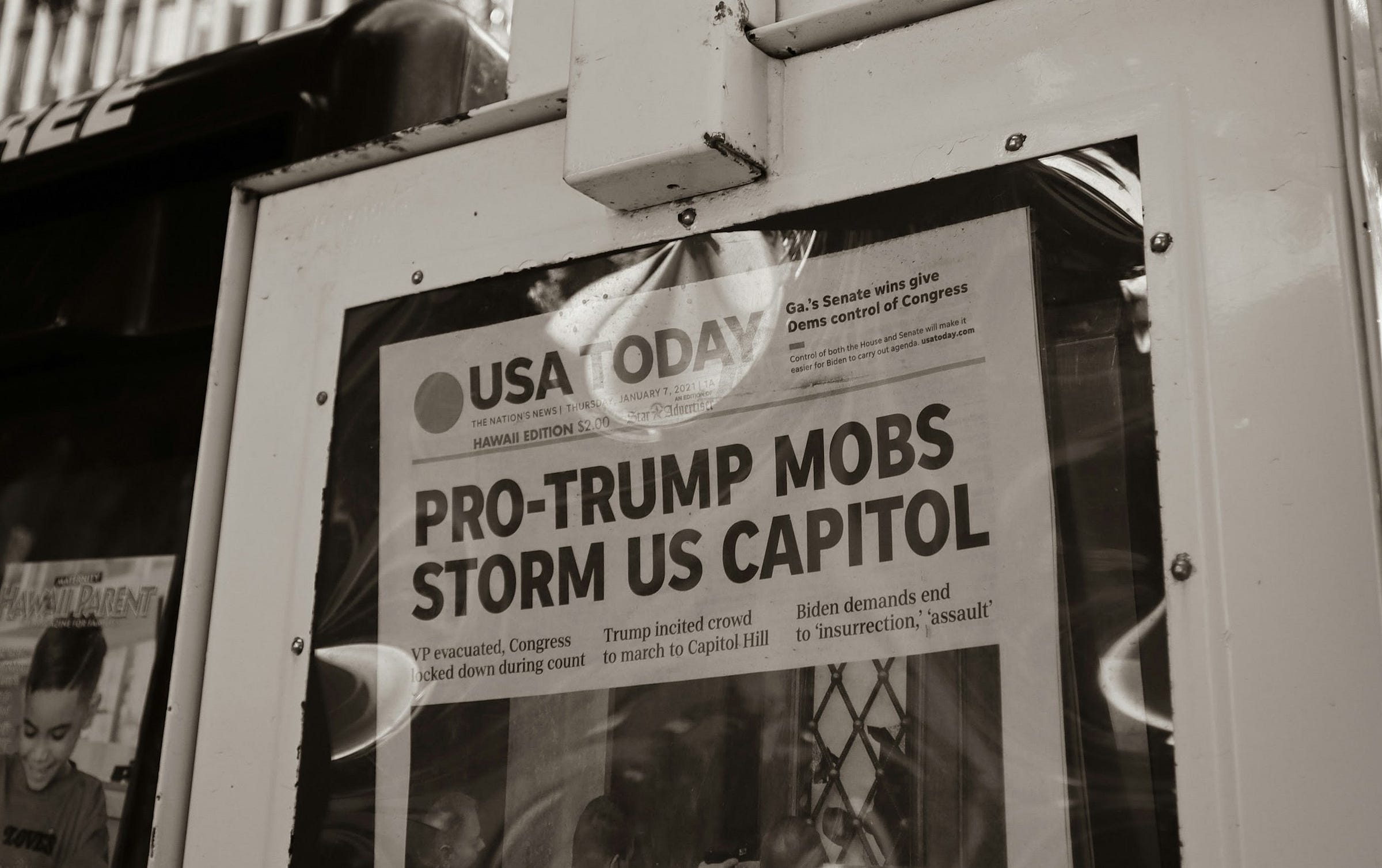

This week saw the great re-writing of both history and of the present moment. On Tuesday of this past week, the White House launched a website that documented their vision of the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capital, though it is difficult to read their version of history and come away thinking the U.S. Capital was ever attacked. The home page displays a glitchy image of Nancy Pelosi hovering over the members of the January 6th Select Committee in stark black and white. The accompanying timeline of events on the website documents President Trump’s “powerful speech,” the “peaceful march” that followed, and how the Capital police “turned a peaceful demonstration into chaos.” It goes on to vilify Mike Pence for “betraying” the president, the United States Congress for certifying the “stolen election,” and the Justice Department for arresting “protestors,” some of whom later died by suicide, their deaths folded seamlessly into the grand narrative of martyrs attacked by a tyrannical government.

On Wednesday, after Renee Good was fatality shot by an ICE officer, the same team who just hours earlier released that January 6th website sought to rewrite the present moment. Kristi Noem declared, two hours after the shooting, that Ms. Good was “a domestic terrorist” who was attempting to ram her minivan into the officers after their vehicles got stuck in a snow bank. President Trump wrote that Ms. Good “violently, willfully, and viciously ran over” the officer who shot her. He added that the officer was nearly killed and was recovering in the hospital. The following morning, J.D. Vance authored a moral footnote: "I can believe that her death is a tragedy while also recognizing that it is a tragedy of her own making."

What distinguishes these events from the Boston Massacre is not moral clarity but technological abundance. January 6th and the killing of Renee Good were filmed—repeatedly, from multiple angles. Both events were, astonishingly, recorded both by the victims—the Capital police and Ms. Good’s wife—and the perpetrators—January 6th rioters and Officer Ross. And yet the presence of video has not constrained the imagination; it has liberated it. We are told, by the likes of Noem and Vance and Trump, to see actions that are simply not there: assaults that do not occur, threats that never materialize. There is no ICE vehicle stuck in a snow bank, no minivan running over an officer, and seemingly no hospitalization of Officer Ross. The lie is no longer a denial of evidence but an instruction to distrust perception itself.

The rhetorical move Sean Spicer made on the first day of Trump’s first term proved to be the underlying ideology for the MAGA movement as a whole. The crowd at Trump’s inauguration was indeed smaller than that of Obama’s inauguration. And Sean Spicer knew it then as did everyone in the Trump coalition. But whether or not they believed it was far from the point. The point was to demonstrate that one could look directly at an image and be told—authoritatively, angrily—that it showed something else. Reality became a loyalty test.

And so we arrive at a moment where videos of a Capital under seige, or the wheels of a minivan turning in the opposite direction of an officer, is no longer evidence but a matter of opinion. To insist on what your eyes report is to be accused of partisanship, of being no better than the other side. The goal is not persuasion but dissolution, it is to erode the very idea of a shared account, a common “there” there. In such a world, history will indeed be written by the winners—but the present, too, becomes a kind of air ball arcing through the moment, waiting to be grabbed, renamed, and declared decisive by whoever gets there first.