THE PREVAILING IMAGE OF MOZART IN POPULAR CULTURE HAS been undoubtedly colored by Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play turned 1984 film Amadeus. The image is one of a silly, fanciful, perhaps spoiled, but nonetheless inspired child prodigy turned adult genius. A naïve phenom. In Shaffer’s work, Mozart laughs, giggles, guffaws, farts, raspberries, carouses; in short, he is not presented as a terribly serious person. In the same way in which he would nonchalantly dash off three symphonies of eminence brilliance in the matter of a few weeks, it would seem that his personality was just as carefree and unaffected. The wit and lightheartedness of his musical lines seemed to embody his own personality: a playful figure whose genius seemed to stunt any kind of deep personal maturation. This stereotyping of Mozart is not entirely off the mark. In reading his letters, one only rarely encounters, if ever, the emotional sturm und drang, the expressive catharsis one sees in the letters of Ludwig van Beethoven for example. Mozart’s darker emotions, what he referred to as his “black thoughts,” were held close to his chest. He hardly ever expressed anything akin to a deep depression.

But in the course of painting Mozart with too broad a brush, as a kind of jolly savant, one misses the complex paradoxes that lie at the core of his music, specifically in his late operas written in collaboration with the masterful librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte. How could a composer, so distant from expressing deep emotional pathos in his personal life, write music which demonstrates an astonishing understanding of the human condition? Mozart, it would seem, throws a wrench into the often incorrect notion that all art is some form of autobiography. We take those passionate, sometimes strikingly morose letters of Beethoven, and set them alongside movements from symphonies or piano sonatas that seem to capture that sorrow or anguish. We assume that great music which conveys grand emotions must have been written in a passionate white heat, if not shortly thereafter once the artist cooled off. But in the case of the three Mozart-Da Ponte operas, Don Giovanni, Le Nozze di Figaro, and Cosi Fan Tutte, Mozart’s complex, multilayered, and empathetic characterization of people who are oftentimes objectively horrid seems to come out of left field. He, in other words, deceives us.

As do his characters. Mozart musically demonstrates a profound understanding of human psychology, notably, that a person can say—or in this case sing—one thing while feeling or intending another. This would seem obvious: characters in operas lie to one another. But it is how Mozart goes about composing that deceit which is both musically and psychologically masterful. The grand contradiction in Mozart’s operas is his deployment of unquestionably beautiful music for characters to sing when they are in the act of sinister deception and manipulation. Reserved like a top shelf bottle of sherry, Mozart breaks out sublime simplicity and beauty for the worst people at their worst moments.

This would seem, on the surface, not to make much sense. Our gut reaction would be to set horrible deeds against a backdrop of equally terrifying music. But in deploying gorgeous music when a character is in the act of manipulating another character, there are two levels of deception at play. The first is the deception which exists in the plot itself. Beautiful music lures and convinces otherwise intelligent characters to believe the lies that are hidden behind the surface. The second, and perhaps most brilliant deception, is a kind of meta deception on the audience viewing the opera. The audience oftentimes knows far more information than the helpless victim on stage as well as the psychological chess game the manipulator is deploying. Nonetheless, the audience seemingly washes that knowledge away when the harmonic motion of a scene cools, melodic lines gently rise, and the orchestra blossoms. The audience is, in most cases, as conceived of the master manipulator’s lies as the character on stage is. The syrupy lushness of the aria takes a hold of the audience, a set of outside observers, as much as Mozart and De Ponte’s characters.

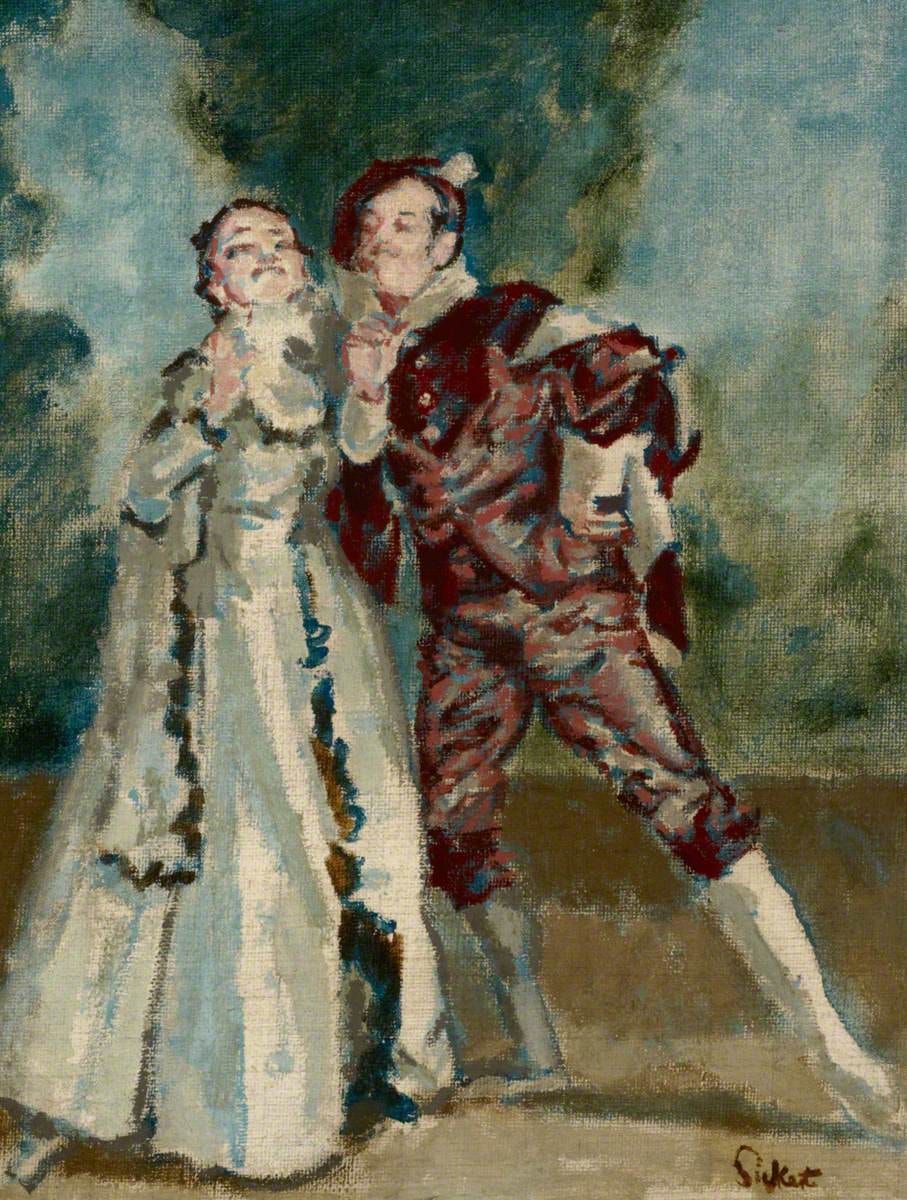

THERE IS PERHAPS NO OPERA MORE OBSESSED WITH THE MARRIAGE of seduction and deception than Don Giovanni. Though often portrayed in older productions or album artwork as a kind of Pepé Le Pew like figure, a suave yet ultimately unsuccessful philanderer, Don Giovanni is no such thing. There is no need to perform some kind of deep reading or close examination of Da Ponte’s libretto or Tirso de Molina’s 17th century play which provided the source material. Any reader, or listener for that matter, can clearly understand that Giovanni is unquestionably not a simple ladies man, but a violent serial rapist and a murderer. The full weight of his depravity is shown in blinding technicolor from the very outset of the opera. After breaking into the apartment of Donna Anna and donning a mask, he attempts to rape the young woman. Minutes later, he murders her father for having the gumption to stand in his way. The message of just the first few minutes of the opera is crystal clear: Giovanni is a sociopath who will kill with ease anyone who gets in the way of the thing he wants. And the thing he wants, more than anything else, is women. He is not a “sexually promiscuous nobleman,” as some online synopsis would want one to believe. But a cold, calculating, and callous rapist and murderer.

For a good half hour or more, we encounter more characters who add color commentary to Giovanni’s past. Not one of these anecdotes contradict the actions of the man we have met. Instead of adding a nuanced set of flesh and bones, the more we learn of him, the deeper we see his depravity. Then Giovanni and his loyal wing-man Leporello happen upon a country wedding, and see two young peasants frolicking in blissful matrimony. When Giovanni eyes the young bride Zerlina, the scene is set like a PBS nature documentary; the lion has set its sights on the gazelle. Everyone viewing the action inevitably knows what will come next.

After engaging in a bit manipulative small talk, Giovanni kicks the seduction into high gear and we, the audience, witness for the first time, his sexual pursuit. What comes out of Don Giovanni’s mouth is unquestionably the most lyrical, beautiful melody thus far in the opera. We have heard wordy patter arias, rage arias, comforting duets, but a simple, straightforward almost folk like tune has been skillfully reserved for this moment.

The famous aria “La Ci Darem La Mano” (There you’ll give me you hand) would seem, out of context, like a precursor to the short, folky strains of a Schubert lieder. There is a steady, unadorned string accompaniment with a similarly modest harmonic language made up of the solid building blocks of nearly all popular music: the tonic, subdominant, and dominant. It sounds almost guitar like in its simplicity, and Giovanni will later in the second act, break out a mandolin and seduce another woman under her window in true bommbox-raised-over-the-head fashion. Indeed, the tune is so closely related to contemporary popular music that Frank Sinatra smoothly covered the aria in a scene in the 1947 musical comedy It Happened In Brooklyn, not in a grand operatic style, but in his buttery croony baritone. The music, unlike the antagonist’s intentions, is plainspoken and direct.

In a way, Giovanni is musically “speaking” in the simple language of the young country woman he is trying to capture. A nobleman, Giovanni is musically donning a folk tune as a method to manipulate someone of the lower class, to essentially speak on her terms. Zerlina, though initially hesitant, gradually succumbs. The American musicologist and theorist Charles Burkhart noted that the rhythm and structure of the aria mirrors Zerlina’s gradual change in outlook. Trading the tune back and forth, Burkhart remarks that Giovanni’s part is “characterized by ever shorter measure groups as he presses his suit with ever-increasing insistence, while Zerlina's part … is most notable for its ever longer extensions as she wrestles with her conscience and stalls for time.” Zerlina is eventually won over and joins Giovanni in a duet, the two singing for the first time in harmony. At this moment of turning herself over, the music suddenly changes affect into a cool yet lively 6/8.

We, the audience, could sit there in the opera house in stark judgement. We have seen this man, whom she has quickly turned herself over to, rape a woman, kill her father, and then heard story after story about this his debauchery. But unlike Zerlina, we know this information. And yet, we too are musically seduced by this beauty. We too have been won over and we, in fact, know better. Even with all the information we know, we are beguiled.

At its best, great art can function as a kind of empathic imagining. Instead of passing judgement on individuals who stay in abuse relationships, or in the case of this moment in Don Giovanni leave a new marriage to enter one, we have briefly caught a glimpse, through Mozart’s manipulative but nonetheless deeply effective music, why that might be. Like Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s “What’s The Use of Wondering,” we briefly embody, at least musically, the complexity of turning oneself over entirely to someone or something that we know will end us.

THE LAST OF MOZART’S OPERAS WRITTEN WITH DA PONTE, COSI Fan Tutte reads like a bad swingers comedy from the 1960s. Two young couples engage in a game of wife swapping, though this sexual switch-a-roo is not disclosed to the woman. The game is part of a cynical and bluntly misogynistic bet wagered between the old philosopher and confidant Don Alfonso to the two men. The soon to be husbands first convince their girlfriends that they have been sent off to war and then return disguised as sexy foreigners to ensnare each others wives in hopes to see if they stay loyal. Meant to prove the folly of feminine desire, both sexes cave to their fantasies in the end.

Fiancee swapping aside, the first in a series of cruel manipulations occurs when the woman are informed that their husbands have been drafted into a phony war. (Somehow Don Alfonso quickly assembles an entire choral ensemble to send them off to sea). The shock of seeing their fiancees suddenly plucked out of domestic life into deadly battle is, understandably, too much to bear. So they, along with Don Alfonso, sing a prayer for the safe return of their lovers.

This trio “Soave sia il vento” (May the wind be gentle) is arguably, along with the Adagio from his Gran Partita K361, the most sublime music Mozart ever composed. The orchestra, like the sea they are staring off into, is placid and vast. The harmonies progress slowly by way of undulating upper strings forming a stream of endless sixteenth notes. The hymn being sung is simple and profound.

After a brief quasi a cappella section, the music suddenly breaks into an icy stillness by way of a fully diminished seventh chord, orchestrated hauntingly in the winds with the violins bringing back the timeless waves of the opening. The chord is alien to the musical vocabulary of this trio, and indeed of this opera, and clashes against all that has come before. Functioning dramatically if not harmonically, the chord sits much like Wagner’s Tristan chord, the famously static yet unstable sonority that governs the emotional terrain of Tristan und Isolde. Both chords seem unable to resolve. In the case of Cosi, the chord falls upon the word “desir,” which is translated either as “wishes” or “desires.” I’m privy to “desires” for more reasons other than the obvious one.

The deployment of this chord on the word “desires” is both an emotional spotlight on the present and a dark premonition of the future. In the present, there are two simultaneous desires being conveyed in this trio between the three singers. The first and perhaps most obvious, is the desire of the two woman, for the safe return of their husbands from a violent war. The second, more illusive, is of Don Alfonso, whose desire relies upon manipulating the two woman and their husbands in this physiological wager. But the chord is also a premonition. It will indeed be all of their desires, the sexual and the philosophical, that will lead to their downfalls. Their fate, much like the unresolved, static nature of the harmony, is immobile.

And yet again, we are confronted with sublime music to occupancy a masterful deception. The music and words are profoundly heartfelt for two of the three singers. The third must wear this sentimental hymn much like Don Giovanni wore simple folk music. The two men, Giovanni and Alfonso, must disguise their inner thoughts and desires as a way to ultimately manipulate their victims. And we, the audience, are once again wrapped up in this deceit as much as the victims on stage are.

THERE IS A POPULAR ARGUMENT, NOT WITHOUT MERIT, THAT MEGA canonized composers like Mozart are almost immune from any real, substantial criticism. Almost. That untouchable, statuesque mold we put Mozart into seems to dissolve rapidly when the topic of his operatic finales are brought up. After an ingeniously crafted evening of dark situation comedy which brilliantly fits the dramatic strictures of sonata form like a glove, comes this oftentimes awkward musical appendage. The drama of the opera has since been closed and now the characters strip their roles, hurtle themselves towards the footlights, and address the audience directly like a Greek chorus. It seems terribly old fashioned: the members of the cast come forward and essentially explain to us that this whole musical enterprise has been a simple morality tale.

After the title character has been dragged to hell in the penultimate scene, the end of Don Giovanni concludes with this text, translated by J.D. McClatchy:

Let the villain rot,

Tied in Pluto’s knot!

Good people all agree.

Come sing joyfully

The oldest refrain there is.

Watch out now for what lies ahead.

A sorry fate awaits each sinner.

He suffers life, and ends up dead.

Like an overly preachy after-school special, the point of the opera—as though there must be one single point—has been handed to us. Bad things happen to bad people. Well, I could have saved us all the last few hours of recitatives, arias, and ensemble pieces if that was the concluding message!

After nearly all of the characters in Cosi have been caught with their collective pants down, figuratively if not literally, this too is closed off with a moralistic coda. The concluding action of Cosi is perhaps more painful, complex, and less in need of a simple morality tale than Don Giovanni. Upon throwing their disguises, the women learn of their fiancee’s plan and, worse off, their infidelity. Conversely, the men have learned a great deal over time about each other’s soon to be wives. The revelation, and all that is implied and unspoken, hangs in the air awkwardly. Like the aftermath of a violent argument between a couple, the broken picture frames and glasses are scattered on the floor with deafening silence surrounding the painfully revealing incident.

And this is how Da Ponte breaks that silence:

Happy is the man who looks

On the bright side of everything,

And in all circumstances and trials

Lets himself be guided by reason

What only makes the others weep

Will be for him a source of joy,

And amid the storms of this world

He will find his peace in every season.

This cheerful “but all will be well” style ending is also foisted upon the characters in the other Mozart-Da Ponte collaboration, Le Nozze di Figaro. How could it be that all three of these operas that treat difficult, dark subject matter with such risky care can so grandly drop the ball at the last minute? This, too, might be a bit of a depiction on the part of the creators. The conventions of the time nearly demanded a bombastic closing number for symphonies, concerti, and operas. Even though the drama here ends unsettled and complicated, the ending needs, almost begs for, a big finale.

But in all the bombast and joyful merriment, there is a kind of neurotic tick below the surface: everything is fine, everything is fine, everything is fine. The very end of Figaro finds the whole ensemble, first muttering then gradually exclaiming “Let’s hasten to the revelry.” Essentially, “let’s put this all behind us and quick!” The problems and revelations are dashed off so quickly and with such blinding, Panglossian optimism to be phony. Indeed, the “true finale” in Figaro—by which I mean when the celebration really kicks into high gear—is only about one or two minutes of music, profoundly disproportional for an opera lasting almost three hours. In a famous, perhaps infamous depending on who you are, production by Peter Sellars, the cast adorns this over the top romp with jazz hands and a line dance.

There is absolutely no way the characters in these three operas think everything is okay. They, like so many people trapped in uneasy situations, just want to simply move on. So they force joy on to themselves. The final lie in each of these operas, works that have been laden with cruel deceit and manipulation, is a lie to themselves.