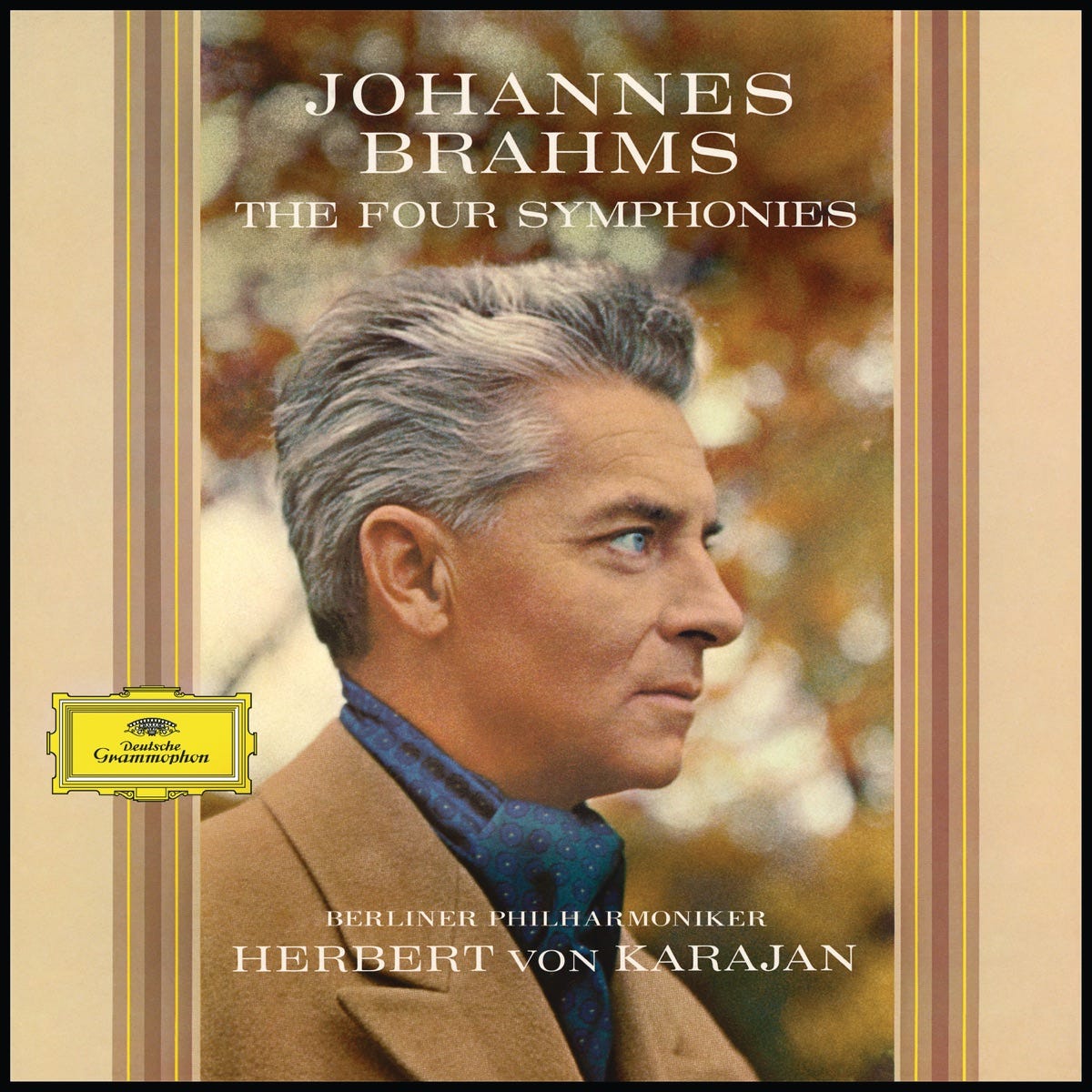

IS THERE ANYTHING AT ALL TO THIS? Even the causal observer of the classical section of any record store—or to venture into the current century, Spotify—has noticed when flipping through the stacks an abundance of autumnal foliage accompanying CDs of Brahms symphonies, chamber music, and piano works. There are leaves strewn across rural country roads or lakes with a reflection of distant maples. Some records directly declare the seasonal connection such as ‘Brahms for Autumn.’ At the moment on the turntable, it is the 1964 recording of his First Symphony performed by the Berlin Philharmonic and Herbert von Karajan, part of a box set of the complete symphonies. The cover features an image of the maestro in profile, his piercing blue eyes, silver mane, and pristine dark blue ascot are set against a blur of orange and green trees in early fall. Same orchestra, forty-five years later. Now Simon Rattle is standing, looking off into the distance with a raised eyebrow and wearing a dark peacoat and, as is apparent tradition, an ascot of grey silk set against, yet again, orange and red and green leaves turning behind the conductor. Perhaps just a simple nod back to the ‘64 recording, or a deeper Brahms seasonal conspiracy?

At the very least, the record companies seem to believe there is a marketable connection with the music of Johannes Brahms and the season of autumn. Is it the signature full and robust beard the composer grew later in life which brings about feelings of cooler weather? Is it the rounded hemiolas that support long melodic lines that makes us feel warm and cozy? One classical radio station theorized it was the late music of Brahms in particular—the clarinet works, the Op. 117-119 piano pieces—that conjured up feelings of fall; the composer’s glance at death mirrored by nature’s own steady stroll towards winter. But would that not also pertain to every composer’s works which were penned during the autumn of their life? Why not pair the operas of Leos Janacek or the late works of Elliott Carter with warm apple cider and Pumpkin Spice? His three early Robert Frost settings would certainly make my fall playlist! Others say it has to do with the days getting shorter, the nights growing longer, and, I guess, the melancholia of Brahms’ failed love affairs reflected back to us.

Major labels aside, I made my own subconscious autumnal connection with the old master two years ago which seems to be coming back now that autumn is in full swing.

I was in Chicago, leeching on to my partner’s free ride to a conference he had to attend. While he got to sit and jot down notes about how to best survey the nation on cultural trends, I got to freely meander around the Windy City for a few days. Since my beloved Chicago Cubs were out of town, I walked my way through the city on what was not the official first day of fall according to the calendar but was certainly the first day as far as the weather was concerned. You could see the sparkle in the eyes of the Pumpkin-Spicers who, after long suffering through false autumnal flags earlier in the month, could now wear their sweaters, cardigans, and light jackets in peace without the fear of a heat wave rudely bulging in on their afternoon commute home. The trees, which had been in the process of turning, were now fully committed to the project at hand. The sunlight seemed to stay a warm orange well into midday even after the typical morning glow had faded. People seemed to take a little more time getting to places, attempting to fully embrace and take in the newly arrived season.

In my zig-zagging through the city, I eventually decided to grab a cheap, day-of ticket to whatever was on the program at the Chicago Symphony. Looking at the program on the outside facade of the hall, I saw that the big second half piece was Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony, a short but bombastic series of Russian folk tunes. (Since Tchaikovsky famously only wrote three symphonies—4, 5, and 6, of course—this didn’t exactly draw me in). But the first piece on the program did catch my eye and future ear, Brahms’ First Piano Concerto with the great Yefim Bronfman conducted by the then music director Riccardo Muti. I bought a ticket and took my seat at the edge of the horseshoe configuration that surrounds the orchestra. Normally, these edge seats facing the back of the piano soloist are littered with piano students writhing back and forth and up and down during the performance to catch the slightest glimpse of a fingering here and there from the performer. I was on the opposite side and able to see both the performance on stage and in the seats across the way.

The orchestra sounded good on the first hefty roar that opens the work, and Bronfman was impressive. But perhaps because of some deep seeded cynicism or too much music school which made me into a knee jerk critic at all times, I found the first few minutes to be just fine. Satisfied, I slumped back and relaxed for the remainder of the movement. If the first movement begins with an orchestral snarl, the second begins with a whisper. In this case, a whisper so intimate and delicate I honest to God had to lean forward! The string section, who first holds a static chord which then morphs into a long melodic line in octaves, was barely engaging the string. There was hardly any sound at all resonating in the hall. The bows seemed to hover over the instruments creating transparent wisps. The pulse, though pretty steady, seemed to evaporate into timelessness. The sound soon blossomed, but still in the haunting transparency of the opening sonority. Both hearing and seeing an entire string section play that intimately—almost like a quintet rather than a full orchestra—was profound. It was the kind of concert experience one dreams about, the kind where one, to make this even more cliched than it already is, loses themselves. The tenderness of the music, the almost vulnerable action of barely making a sound at all, created a physical sense of yearning. When the soloist entered with an equally introspective solo response, it didn’t feel like it normally does on most recordings. On most recordings, it feels like the camera zooms in on to a lonely individual after hearing a lush mass. But here, it sounded as though the pianist was on emotional par with the orchestra; two musical entities juxtaposed.

The rush of autumn air hit once I left the performance. The Tchaikovsky had been an aural slap in the face, as expected, but I was still thinking about that second movement in the Brahms. And I walked through the red and orange and yellow trees on Michigan Avenue in a kind of trance, to bust out yet another cliche.

I find that my most vivid memories, the ones that I can recall without any mental interruption, are the ones associated with the change in seasons or with the music that was playing at the time. Long car trips are etched into my memory because of the music that was being played in the background. State fairs and school letting out at the end of the year are all the more evocative because of the sudden shift in the weather. This moment in Chicago had both, shifting the memory into the realm of the profound, whether it truly was or not.

The record companies and I are now on the same page it would seem! Brahms and fall are now intertwined in my consciousness. Reflecting on all of this, I have come back empty handed in my investigation and the mystery continues. Maybe it is the beard after all, or the inner lines that extend over the bar? I guess we can rule out the late works now since the first piano concerto was his first significant foray into the orchestral genre. What ever it might be, I no longer question it. It just is.